Immobility

Mobility is a cornerstone of human activity, which is important not only for physical activity but also for maintaining overall health and well-being. Instability, whether due to illness, injury, or other circumstances, can have a significant impact on a person’s quality of life. In this section we will explore the critical importance of mobility, delve into nursing knowledge with a focus on mobility and movement, and examine the systemic consequences of immobility. By the end, you will have an in-depth understanding of the clinical implications of immobility and how to effectively manage the challenges. Let’s take a closer look at these interacting aspects.

By the end of this section, you should know about:

- The importance of mobility in human activity

- Nursing skills based on navigation and movement

- Systemic Effects of Immobility

- Clinical significance

Let’s take a closer look at them.

Test Your Knowledge

At the end of this section, take a fast and free pop quiz to see how much you know about Immobility.

The importance of mobility in human activity

Travel is important for a variety of purposes, including emotional expression, meeting basic needs, safety, daily activities, and recreation. The musculoskeletal system must be functioning properly in order for him to be able to move around. Nurses play a vital role in the management of mobility and immobility through scientific and practical strategies to ensure quality care.

Movement and body mechanics

Movement is a complex interaction of muscles and bones and muscles. When assessing body movement, nurses should consider the physical and mental state of the patient. Appropriate body mechanics, including alignment, balance, and transfer of forces such as gravity and flexion, are essential for safe patient handling and prevent caregiver injury Evidence-based approaches are now preferred over traditional lifting practices.

Symmetry, balance, and gravity

Body alignment promotes stability and reduces stress, helping to strengthen muscles and conserve energy. Balance is important for both regular and dynamic activities. Factors such as illness, aging, medications and limited mobility can compromise balance, increasing the risk of falling. Gravity affects the center of gravity, and friction can damage the tissues if not managed during patient handling. Mechanical devices such as slings reduce the risk to patients and caregivers.

Skeletal Structure and Motility

The skeleton provides structure, protects vital organs, and provides flexibility over associated muscles and tendons. Bone strength and density change with age, leaving older adults more susceptible to conditions such as osteoporosis and fractures. In addition, bone optimizes calcium metabolism, produces red blood cells, and stores blood, linking bone health to overall mobility and strength.

Muscles, tendons and tendons of Immobility

Bones connect bones and allow for a variety of movements, while muscles provide flexibility and support for joints. Tendons attach muscles to bones, allowing them to move, and cartilage inserts into the joints, although they become weaker with age. These systems work in concert for locomotion, and their disruption can be devastating to exercise.

Skeletal muscle and nerve coordination

Skeletal muscle controlled by the motor nervous system is essential for movement. The motor cortex in the brain controls voluntary movement, and disruption of this system—through injury, trauma, or disease—leads to loss of mobility, balance, or posture

Effect of diseases on motility

Navigation issues arise from a variety of situations:

Abnormal posture: Conditions such as scoliosis or lordosis affect alignment and balance. Nurses work with physiotherapists to improve mobility and strengthen muscles.

Neurological diseases: Diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis cause progressive muscle degeneration, limiting mobility.

Central Nervous System Damage: Brain or spinal cord injury impairs function and voluntary movement, leading to conditions such as hemiplegia or balance problems

Injuries to the musculoskeletal system: Fractures or injuries can cause temporary or permanent mobility issues, requiring alignment, stabilization and rehabilitation.

Hemiplegia: Paralysis on one side of the body, typically caused by a stroke or neurological injury.

Posture: The position in which the body is held while standing, sitting, or lying down, affecting musculoskeletal health.

Mobility: The ability to move freely, easily, and independently, including walking, sitting, and transitioning between positions.

Body alignment: The positioning of the body in a way that the musculoskeletal system is in a neutral, balanced position, preventing strain and injury.

Body mechanics: The use of correct posture and movement techniques to reduce stress on muscles and joints, ensuring safe movement and preventing injury.

Exercise: Physical activity that helps maintain or improve strength, endurance, flexibility, and overall health.

Friction: The resistance encountered when two surfaces rub against each other, which can lead to skin damage or pressure ulcers if improper care is taken during patient handling.

Immobility: The inability or restricted ability to move, often due to illness, injury, or medical conditions.

Nursing skills based on navigation and movement

To ensure optimal care for patients with mobility challenges, nurses must incorporate scientific principles of mobility and stability into clinical practice. Mobility ranges from complete freedom of movement to complete immobility, with associated physical and psychosocial impacts.

Key Concepts:

Factors affecting trip-level: Continued improvement in mobility: Patients can range from complete ambulation to complete mobility.

Bed rest: Although prescribed for medical reasons, prolonged bed rest can have adverse effects, such as muscle rest, where muscle strength decreases by up to 3% per day.

Bed rest: A prescribed period of rest in bed, often for healing after surgery or injury, limiting movement to promote recovery.

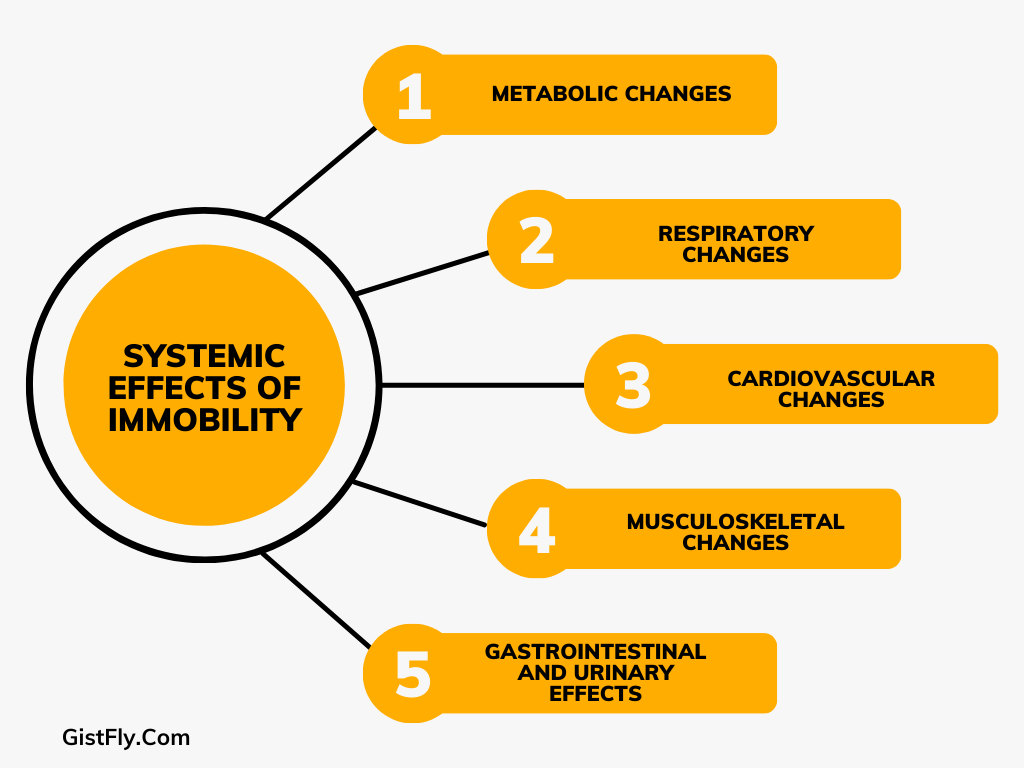

Systemic Effects of Immobility

Metabolic changes: Metabolic alterations: metabolic decline, calcium reabsorption, and gastrointestinal function. Nitrogen imbalance: Protein breakdown leads to muscle loss and weakness. Calcium loss: Increased calcium absorption can lead to hypercalcemia and fibrosis.

Respiratory changes: Risk of complications: Lack of mobility increases the risk of atelectasis (alveolar collapse) and hypostatic pneumonia (swelling from the accumulation of fluid in the body). Decreased copper potency: accumulation of water promotes bacterial growth.

Cardiovascular changes: Orthostatic hypotension: A sudden drop in blood pressure when walking in an upright position. Increased cardiac work: Decreased efficiency leads to increased oxygen demand. Thrombus formation: associated with Virchow’s triangle: tissue damage, changes in blood flow, and changes in hemodynamics.

Musculoskeletal changes: Muscle Effects: Protein breakdown can lead to muscle weakness, decreased endurance and increased risk of falls. Orthopedic Effects Bone disuse and narrowing of joints (e.g., foot drop) can lead to permanent deterioration. Fracture prevention: Early intervention with positioning, range of motion (ROM) exercises, and splints can reduce risks.

Gastrointestinal and Urinary Effects: Constipation: Decreased peristalsis and urinary retention may cause urinary retention. Fluid imbalance: Lack of fluid and decreased intestinal mobility can worsen the outcome of constipation.

Thrombus: A blood clot that forms within a blood vessel, often due to immobility or poor circulation.

Atelectasis: A condition where part of the lung collapses, often due to immobility, leading to reduced lung expansion and impaired gas exchange.

Clinical significance of Immobility

Prevention and control measures: Collaborative care plans: Preparation of private travel contract restrictions on admission. Include ROM exercises, positioning and splinting when necessary. Patient Education: Emphasize the importance of walking in preventing complications. Encourage active exercise within safe limits. Monitoring and Emergency Intervention: Routine screening for signs of stability-related complications (e.g., DVT, pneumonia). Use early stimulation exercises and therapeutic exercises to restore function and independence. Equipment and Staff Training: Ensure availability of harnesses and other assistive devices and provide instruction for their proper use.

Urinary, bowel, psychosocial, and developmental changes due to immobility

Changes in urine output Fluid Stagnation: Stasis blocks the flow of gravity, causing the kidneys to accumulate in the pelvis and: urinary tract infections (UTIs) due to immobility. Renal arteries: Hypercalcemia is common in critically ill patients, leading to stone formation. Risk of dehydration: By decreasing fluid intake, fever increases dehydration and increases dehydration, increasing the risk of infection infection and stones increase.

Changes in the muscles Pressure ulcers: Prolonged pressure on the prominent bones can lead to increased anemia and eventual skin loss. When external pressure exceeds the arterial pressure, arterial ischemia occurs due to reduced blood flow. Preventive measures: Frequent repositioning, use of pressure-relieving devices, and maintenance of skin integrity are essential to prevent costly and difficult-to-treat scarring.

Psychosocial consequences Emotional and behavioral responses: Fixation increases depression and withdrawal, often driven by concerns about health, finances, and the future. Isolation can increase feelings of loneliness and depression. Emotional changes: Patients experience mood changes, sometimes reducing emotional motivation to engage in care.

Changes in development Babies, toddlers and preschoolers: Immobilization delays significant motor, cognitive, and musculoskeletal growth. Common causes include congenital anatomical abnormalities or dementia requiring immobility. Young people: Decreased activity also affects basic areas such as independence, social mobility, and mobility. Issues of social isolation and body image arise. Adults: Status affects role and identity, and potential job loss affects self-esteem and financial well-being. Older Adults: Loss of bone mass, decreased productivity, and slowed movement lead to falls and dysfunction. Hospitalization and immobility exacerbate physical dependence and psychosocial impact, often precipitating long-term disability.

Basic implications for nursing of Immobility

Hydration Plan: Encourage hydration and check for signs of infection or stones. Skin integrity: Implement and educate caregivers on pressure ulcer prevention techniques. Psychological support: Provide emotional support and encourage social interaction to combat isolation and depression. Developmental Considerations: From encouraging play in children to promoting independence for older adults, she looks at age-specific programming resulting from children with limited mobility the solution of the. Nutritional assessment: Ensure adequate nutritional intake to support body reprogramming, especially in older adults.

Understanding nursing assessment of mobility

The nursing approach to mobility assessment focuses on assessing the patient’s ability to move, identifying any limitations, and identifying risk factors associated with immobility. This assessment combines subjective information from the interview with objective physical examination to ensure a thorough understanding of the patient’s developmental status.

Collecting subjective data: Identifying changes in mobility

The assessment begins with the collection of patient travel information. Questions can focus on changes in movement, joint discomfort, or difficulties with daily activities such as walking or standing. This step also examines the patient’s perception of limitations, whether due to a chronic condition, sudden injury, or lifestyle. Understanding the timeline and context of these changes is critical for designing interventions.

Range of motion (ROM) assessment of Immobility.

Assessing ROM is a cornerstone of motion assessment, helping to determine joint flexibility and muscle function. Patients can engage in active movement, or the patient’s ability can contribute to passive exercises for short periods of time. The ROM is tested in three main planes: sagittal (anterior and posterior), anterior (side to side), and transverse (rotational). A few wrinkles can indicate conditions such as arthritis, varicose veins, and nerve damage. Regular maintenance and mobility are necessary to prevent complications such as slippage or deformity.

Gait research: Balance and movement planning

By observing the patient’s gait, balance, posture, and overall mobility can be studied. Nurses look for things like leg length, walking speed, and mobility. Changes in gait may indicate musculoskeletal, musculoskeletal or systemic issues. This assessment also identifies risk factors for falls, triggering interventions such as physical therapy or assistive devices.

Measurement of functional tolerances

Functional tolerance refers to how much physical exertion a patient can handle before experiencing discomfort or discomfort. During this work, symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest pain can be monitored. Emotional and developmental factors such as anxiety, aging, and pregnancy also affect tolerance. Regular assessments help adjust care plans to the patient’s current capabilities and promote incremental improvement.

Body alignment assessment for postural health

Alignment is assessed in various postures—standing, sitting, or lying down—with perfect alignment of the head raised, straight shoulders, and balanced spine to identify postural information standing with potential muscles or nerves. For patients with immobility or unconsciousness, alignment can be seen in the supine position. Distractions such as shoulder asymmetry or hip asymmetry can indicate prolonged musculoskeletal dysfunction or imbalance that requires targeted intervention.

To ensure proper care through inspection

Together, these assessments provide nurses with a comprehensive view of patient mobility and risk factors. This comprehensive understanding helps develop a personalized care plan that improves mobility, prevents complications such as pressure injuries or ulcers, and promotes overall wellness. Regular reassessment ensures that care plans adapt to changes in a patient’s condition, maximizing efficiency.

Habitat: Body alignment and risk reduction of Immobility

It is important to live a healthy lifestyle for comfort and health. The head should be stable, the neck and spine straight. Body weight should be evenly distributed between the hips and thighs, with the thighs parallel to the floor. The feet should be well supported on the ground, or footrests may be necessary for smaller individuals. To avoid pressure on the popliteal muscles and tendons, allow 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in) of space between the edge of the chair and the back of the knee. Elbows should rest on elbows, hips, or tables. For patients with muscle weakness or muscle damage, proper alignment is important to avoid complications.

False: Comfort and safety and compatibility assessment

When evaluating a patient in bed, the lateral posture provides a better visualization of body alignment. Remove assistive devices except head pillows, and use a proper mattress for comfort. When properly aligned, the spine merges into an uncomfortably straight line. Patients with neurological disorders or sensory injuries need constant monitoring to avoid pressure injuries or other complications.

The risk of immobility: a comprehensive review

Metabolic effects: Assess muscle weakness by anthropometric measurements and water balance by recording intake and excretion. Monitor diet, food preferences, and wound healing to identify nutritional deficiencies or metabolic imbalances.

Respiratory complications: Limited activity increases the risk of pulmonary problems. Observe chest movements and listen for cracking or discomfort, paying close attention to the dependent areas of the lungs. Look for signs of pneumonia including a productive cough, fever, and dyspnea.

The heart changes: Monitor blood pressure, heart rate, and peripheral rhythm. Orthostatic hypotension and muscle instability are common concerns. Look for signs and symptoms of DVT, including inflammation, changes in skin temperature, and calf circumference. Document and report abnormalities such as weakness or absence of heart immediately.

Musculoskeletal changes: Loss of mobility reduces muscle strength, tone, and size. Check for abnormal appearance of hair and follicles. Be careful not to use osteoporosis in those at risk, as this increases the chances of fracture.

Integumentary and systems of removal: Frequent skin care is necessary to prevent tension, especially in patients with severe conditions. Monitor hydration and bowel function to reduce risk factors such as urinary tract infections and constipation.

Cognitive and developmental outcomes of Immobility

Prolonged immobility can lead to emotional complications such as depression, boredom, and isolation. Watch for behavioral changes, sleep shifts, and signs of withdrawal. For children, restriction of mobility may result in temporary developmental delays, while older adults may experience a decreased level of independence and function.

Preventing risks through nursing diagnosis

Common nursing findings for critically ill patients include poor physical outcomes and risk of disuse. Assessment of relevant factors such as pain or reluctance to move guides interventions. For example, patients with pain may need relaxation equipment to maximize their mobility, while those who are immobile may benefit from encouragement and self-care activities.

Nursing diagnosis and patient care

After her hip surgery, Ms. Carmela Cavallo, 97, suffers physical developmental impairment due to musculoskeletal damage and severe pain during movement although her surgical incision is healing well and she has no heart or blood pressure issues. denies the pain of the knife, thereby severely limiting his transfer or ability to walk. He would like to regain mobility but is having difficulties due to pain.

Objectives and expected results

The primary goals of care are pain relief and improved mobility. Pain relief is aimed so Ms. Cavallo feels less than a 6 on the pain scale when moving. Independence should be transferred from bed chair to bedside commode within five days to gradually improve mobility and use of support. Discharge allows him to walk about 100 yards by walking, increasing this distance each day.

Planned interventions and reflective thinking

Effective pain management is regular prescriptions based on her needs, adjusted based on her response. The collaborative approach includes physical therapy to establish safe transfer techniques and incremental goals for walking. Teaching strategies including oral instruction and reteaching strategies in a distraction-free environment ensure that Ms. Cavallo understands his plan of travel.

Group Work and Maintenance of Immobility

Care involves a multidisciplinary team, including physical and occupational therapists, who guide strengthening exercises and help relearn daily functions with early release to ensure continuous in-home care, with in-home treatment and other necessary services depending on his residential recovery and development

Assessment

Through the pain of Ms. Cavallo understands the timing of his movements and his ability to turn and turn and determine progress. Improved pain control, a gradual increase in ambulation, indicates success. His ability to walk 200 feet with a walker indicates he is more comfortable and ready for a new level of independence.

Health promotion activities

Health promotion includes interventions such as education, prevention, and early detection to increase mobility and address recovery issues. These activities can include prevention of work injuries, promotion of physical activity, fall prevention strategies and early detection of conditions such as scoliosis

Prevention of occupational injuries

Occupational injuries have increased in health care settings, particularly nursing homes, and musculoskeletal injuries such as strained backs are the main concern These injuries are often caused by improper lifting techniques when patients cannot be moved or positioned. To reduce such injuries, healthcare facilities have implemented ergonomic designs and systems that limit lifting, and have advocated the use of assistive devices and patient lifting teams to reduce the stress of ensuring that employees follow safety procedures is critical to protecting patients and healthcare professionals.

Encouraging physical activity of Immobility

Physical activity is important to maintain mobility, especially for those at risk or already at risk of mobility impairment. It improves strength, flexibility and endurance, and can help prevent diseases such as cardiovascular issues and diabetes. Nurses can guide patients in selecting appropriate exercises for their health needs. For example, individuals with knee osteoarthritis may benefit more from hydrotherapy than from traditional walking. Cultural factors should also be considered when suggesting exercise recommendations, as different cultures may have preferences for unique exercises such as dancing or gardening

Bone Health Osteoporosis

Patients with osteoporosis need targeted health promotion to prevent fractures to improve their quality of life. It is important to encourage screening, encourage a diet high in calcium and vitamin D, and recommend weight-bearing exercise. For patients with existing osteoarthritis, education about fall prevention and creating a safe home environment is important. In addition, addressing emotional health by promoting a positive self-image can help manage the psychological aspects of living with osteoporosis.

Anthropometric measurements: Measurements of the human body, such as height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference, used to assess nutritional status and overall health.

Gait: The manner or pattern of walking, which can be assessed to identify mobility issues.

Gait belt: A belt used to assist patients in walking or transferring, providing a secure hold for the nurse or caregiver to help prevent falls.

Take the Pop Quiz